The silo has come West and is taking a place on every practically conducted stock or dairy farm. The first silos that were built cost so much that the practice of putting them up received a serious setback. Now, very good ones are made, and seem to answer every purpose, that can cost only $100 or little over. In Minnesota and Iowa, stave silos are being put up for from $100 to $125, to that will care for from ten to twelve acres of pretty thickly grown fodder corn, or from eighty to ninety tons of good feed. These silos are made of 2x6 stuff, stood up stave fashion and fastened by hoops of rod iron. The outside is kept well painted and the inside well and frequently smeared with coal tar heated till thin and penetrating. (The Saint Paul Globe, Monday Morning, March 10, 1902, Volume XXV, Number 69, Page 8)

Page 220. The Brick Silo. By Forest Henry, Dover, Minn. The silo has come to stay. It is no longer an experiment. No up-to-date stockman can any longer question its practicability. The question now is: What kind of a silo is best and cheapest? The same rule that applies in other things applies to the silo. The best is the cheapest. We need a silo that is strictly air-tight, so constructed as to practically keep out frost and of such dimensions and form as to be best suited to the purpose. The secret of keeping silage is the same as with all canned goods - keeping it from the air. When corn goes into the silo and all surrounding air shut out, it simply cannot spoil. Freezing. With the double walled brick silo, lined with cement, you have a silo strictly air-tight. This is not all, it is also sufficiently warm so as to freeze but very little in the coldest weather. Some will say that it does not hurt silage to freeze. This may be true, but it is mighty unhandy to have to chop it out. It must then lie around in the cow barn until it thaws out, for no one would care to feed it in a frozen state. For my part, I want a silo as warm as I can have it, and then I will place it on the south or east side of a barn where it will not be exposed to the northwest winds and where it will get all the bright warm sunshine possible.

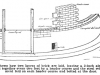

Page 222. Height of Silo. Again, the form has a great deal to do with the usefulness of a silo. It makes no difference whether you are a dairyman with ten cows or fifty, you want a high silo, for the man with ten cows feeds just as many days in the year as the man with fifty, and a little should be taken from the surface each day or every two days at most to get the best results. This is one reason why the brick silo is bound to take first place among the different kinds of silos. You can lay a brick silo high and narrow without danger of its blowing over. The tendency of all silo builders is to build silos too wide in proportion to their height. If I did not expect to keep more than a dozen cows I should not build a silo less than 36 feet deep. Silage packs more in a deep silo and therefore keeps better and with the narrow silo you can feed winter or summer, and always have fresh silage free from mould. Brick silos when properly constructed will keep the silage perfectly clear to the walls. The hollow air space keeps the frost from working through and is therefore an insurance against mould and frost. Construction. In constructing a brick silo it is quite necessary to get the foundation wall below the frost line. For this reason I should excavate about five feet and begin the wall below the frost line. Where stones are handy, I should lay the first six feet of stone. This would bring the stone work a foot above the ground which is not too high to grade up to. In building the stone foundation great care should be exercised to get the wall perfectly true and round, and of the exact size so there will be no shoulder to hold up the silage where the brick joins the stone. I should, by all means, lay the foundation in good rich cement mortar. Lime mortar is worthless below ground. We will next begin to lay the brick. Nothing short of a first-class brick layer should be employed for the work must be done well. The outside course is laid flat, then a two inch air space is left and the inside course is set up edgewise. This gives a four inch wall on the outside and a two inch wall inside with a two inch air space between. These walls are plastered on each side of the air space as fast as the walls are laid. Reinforcement. When the walls are raised two feet high, a header course of brick is laid crosswise to bind the two walls, and on this header course is laid a plate of steel made for the purpose of reinforcing silos and cisterns. This plate of steel goes around the silo except the doorway.

Page 223. On either side of the doorway is a door jamb running from the bottom to top. The plate of steel is turned up about four inches and has a hole near the end through which is inserted a heavy bolt that extends across the doorway, making a strong ladder and at the same time connecting the two ends of the band of steel. This band of steel is put into the wall every two feet until the top is reached. This adds great strength to the silo. The Roof. When a point within a foot or sixteen inches of the top of the silo is reached, bolts are laid into the wall which will hold down a plate to which the roof is spiked. I should use a little cement in the lime mortar in laying the bricks, as it makes a much better wall. Where this is done it is best to thoroughly sprinkle the bricks with water before laying as the mortar dries too rapidly when the bricks are dry. The staging is built in the inside and raised as fast as the walls go up. The roof should be put on as soon as the walls are laid. The roof can be made of either shingles, planks or boards. In using planks or boards each board should be sawed cornerwise and put on with the point up. A shingled roof means considerable work and expense, and a plank or board roof will answer the purpose very well. Do not use metal as it will rust from the lower side and soon be worthless. The patent rubber roofs are not lasting. The very best that I could buy seven years ago is now nearly worn out. This was put on a shed where it can easily be renewed. A silo is a difficult building to reach, and substantial roof should be put on to start with; but it need not be expen-

Page 224. sive. Give the roof a good pitch so that a man will have plenty of room to stand when the silo is level full. If you do not get the roof on while the staging is up, put it on the day you have the silo freshly filled before the silage settles. This is not always convenient as one has not usually the time then, and for this reason would by all means do it while the staging is up. The Walls Are Plastered. The walls are plastered on the inside with two coats of cement mortar. This mortar should be very thoroughly mixed dry, in proportion of one part cement and two of clean sharp screened sand. The staging is lowered as fast as the plastering is completed. In fact, the inside of the silo is finished up just as you would plaster a cistern. Bottom. I would put on a coat of about two inches of cement mortar over the bottom, except a small space in the center. This is not absolutely necessary, but it is nicer and costs so little that it will pay you in the long run. There should be no water to leak away in silage put up at the proper stage, but for fear one might get it in a little greener than he intended some year, I would leave a space two feet across not cemented at the center, and then by having the floor slope toward the center any surplus moisture would naturally leak away. A brick silo properly constructed is not only the very best silo made, but will last a lifetime without that constant attention that must be given the stave silo which at the best will in time rot out. As to the cost you will find, while it costs slightly more at the beginning, when you take its lasting qualities into consideration, it is the cheapest silo that can be constructed. It has no hoops to get loose or paint to wear off. It is a perfect silo for a lifetime. Get Good Workman. It is best if one is building to hire a man that has had experience in laying a silo before to superintend the work. If several were to unite in one neighborhood the expense of an experienced man for a few days would be very light. Do not, however, let some man attempt it unless he knows what he is about. It is one of those jobs that must be done right. Do not be satisfied with anything short of the very best job that can be done. One more word. The only thing I dislike about the brick silo described, is that it is a patent concern and the fixtures have to be bought of the patentee. He is a very practical common-

Page 225. place man, however, and charges only a reasonable amount for the materials furnished. He also furnishes free a large building plan giving the details of construction as shown in the accompanying cut. (Minnesota Farmers’ Institute Annual 1909, Number 22, Edited by A. D. Wilson, Webb Publishing Company, St. Paul, MN, 1909)

MAKING SILOS OF CLAY. The recent rapid change in the relative cost of wood and masonry seems sufficient to have revolutionized building. This has been partially prevented by the lack of knowledge of the new materials and the tendency of humanity to jog along in the same old rut. There is ample talent in existence to solve the problems which these conditions bring about, but it takes time. The man who raises crops knows that in order to even make expenses and interest on the investment in the land at prevailing high prices, he must market more stuff than he did 10 years ago. All intelligent and reading farmers also know that the use of a silo will help very largely to bring about the changes necessary in the production of profit from high-priced land. The use of the silo not only enables the farmer to realize practically twice the nutritive value from the corn crop that the old methods permitted, but it also enables him to keep twice as much stock to the acre, as is possible without it. This stock increases the fertility of the land. In this way the products of the soil are marketed in a more condensed form, thus reducing the loss from the soil and at the same time yielding greater profits. However, practically all that the farmer knows concerning the building of silos is what he sees on his neighbor’s farm, is told by an agent or reads in his papers.

On the other hand the clayworker realizes very fully the great possibilities of the hollow-block construction but seldom is acquainted with the need for permanent silos at a reasonable cost. Thus the supply and demand very often miss connections. The writer, being connected with the Agricultural Experiment Station of Iowa, has for several months been privileged to work upon this particular subject of silo construction and with the help of his friends of the college, and clay industries, 13 silos of the following description have been erected and used. The most common size is 16 ft. in diameter, inside, by 35 ft. in height. The walls are 4 or 5 ins. in thickness, laid up in cement mortar, and thoroughly reinforced in the mortar joints. The door frame is composed of reinforced concrete, which is thoroughly connected with the reinforcing system of the walls. The roofs have generally been made of reinforced concrete. The doors, which are not permanently connected in any way with the building, are made of wood, and when decayed may be replaced at a cost of but $5.00 or $10.00. This replacement need not occur oftener than every five or eight years.

The cost of these silos has in no case been greater than that of the average stave silo which is on the market today. It serves the purpose at all times and in all cases and does not require particular care for maintenance; neither does it deteriorate as rapidly. A visit to all of these silos during the latter part of the extremely cold winter showed conclusively that the block walls were perceptibly warmer than ordinary stave construction, and did not so readily permit the freezing of the silage. The most satisfactory size of material used has been 4x8x12 in. hollow block built approximately to a circle of 8 ft. radius. The bending of these blocks has been accomplished by a very slight variation of the standard machines, thus causing practically no increase in the cost of production. The only difference between the price of this material and the standard is, that the silo block must all be burned very hard on account of the fact that they are subjected to the worst of weather conditions. The accompanying photograph gives a very good idea of the appearance of one of these silos. During the coming summer several more will be built, which will serve not only as silos, but as towers for elevated supply tanks. (Brick and Clay Record, Kenfield-Leach Company, Chicago, IL, November 1910, Volume XXXIII, Number 5, Page 191)

Page 63. Silos and Silage. By A. D. Wilson. Many a Minnesota farmer has now reached the place where the expenditure of a few hundred dollars on a silo will not only prove a good investment in itself, but will render more productive considerable quantities of other capital already tied up in land and live stock. We fully realize that there are many farmers not so situated as to make it advisable for them to build silos; but since the number who can well afford and should have silos is increasing, we wish to call attention, at this time, to several of the fundamental principles regarding silos and silage. The erection of a silo means an advanced step in animal industry. As a general rule, a man with twelve head of cattle, or less, can hardly afford to build a silo. Neither can a man with a larger herd of cattle afford to build a silo, unless he is prepared to keep reasonably good stock, and to take good care of it. In other words, we believe that, by poor management of stock, one can lose more money on a given herd if he has a silo than without; on the other hand the man who has a reasonable-sized herd of good stock, and plans to take good care of them and to make the most out of them, cannot well afford to be without a silo.

Some Advantages of a Silo. A larger proportion of the corn crop can be stored in the silo, in a form suitable for feed for live stock, than can be saved in any other way. Silage is a very convenient form in which to feed a portion of the corn crop. The trouble of handling corn-stalks in the manure is obviated by the use of silage, since they are consumed, with the rest of the plant, in feeding. Silage is excellent feed for any class of stock, with the possible exception of hogs and poultry. Some succulent feed is essential to the most successful stock-growing during out long winters; and silage affords the cheapest succulent feed available for a farmer with a good-sized herd of stock. Feed For Live Stock. Like other states, Minnesota is occasionally subject to a scarcity of rainfall during the crop-growing season, which often results in a shortage of hay and pasture. Minnesota has reached the stage in her agricultural development where continued success in agriculture must depend quite largely upon keeping on all of the farms a larger amount of live stock

Page 64. than has been kept in the past. If live stock is to be profitably kept, a reliable source of feed must be at hand. We need to grow clover and other grass crops to maintain our soil; and in seasons when these crops yield well, they furnish an abundant and economical supply of feed. But, in adverse years, the supply of this kind of forage is limited and expensive. Place of the Silo in Minnesota. Minnesota is rapidly coming to the front as a corn-producing State. It also ranks among the best in the production of hay, clover and other forage. Owing to the fact that corn is a cultivated crop, and persistent cultivation enables one to grow a reasonable crop with a minimum amount of moisture, corn is the surest crop we have. If one has a silo at hand, in which a portion of the corn crop can be stored, he is then practically assured of sufficient forage for his stock. If pastures are short, they can be supplemented by silage. If the hay crop is short, more silage can be fed, and stock carried over satisfactorily with a very small amount of hay. With a silo of ample size, one can then be practically assured of feed at all seasons. When hay and pasture crops are abundant, a portion of the silage stored can be carried over to other years, when there is a scarcity, and with practically no loss. With these facts in mind, it seems evident that very few farms, carrying the stock they really need to maintain their productivity, can longer afford to neglect the silo.

Definition. A silo is an air-tight, or practically air-tight, receptacle for the storage of green fodder to be fed to live stock. A silo may be a pit in the ground, or a stone, wood, brick or concrete building, of almost any size or shape. The modern type of silo is usually built round, of any of the materials mentioned, and very much higher than it is broad. Green forage, usually corn, is run through a cutter and run into the silo, where it is preserved in its succulent form, simply by protecting it from the air. A small amount of silage will spoil on top of the silo, but the mould formed by this spoiling seals up the top of a silo and protects the silage beneath. Any small hole in the wall of a silo, letting in a small amount of air, will cause some of the silage to spoil; but the spoiling is limited by the fact that the mould thus formed seals up the hole. Cost of Silos. A modern silo, made of brick, lumber or concrete, of sufficient size for an ordinary farm, will cost from $200 to $700 or $800; depending, like all other buildings, on the cost of the various materials, the cost of labor, and the style of construction. Good silos, of from 100 to 150 tons capacity, may be erected at between $2 and $4 per ton. From $200 to $500 seems like a considerable amount to put into a building for storage only; but there is no other convenient way of storing forage by which the same amount of feed can be stored more cheaply. The point to consider in erecting any building, usually, is not how much it will cost, but whether or not it offers a good investment. The first cost is not always

Page 65. important, either. The annual cost, which includes the amount of depreciation and interest on the investment, is the real measure of the cost of the silo. If a silo cost $300, and money is worth 6 per cent, and the silo will last 15 years, the annual cost of the silo will be the sum of the depreciation, $20, plus interest, $18, or $38 in all. If a silo costs $400, and money is worth 6 per cent, and the silo will last 40 years, the annual cost will be the sum of the depreciation, $10, plus interest on the investment, $24, or $34 in all. Cost of Silage. Silage is not the cheapest form of feed. When good crops of clover or alfalfa can be secured, enough nutrients to supply the needs of an animal can be secured, as clover or alfalfa hay, at a less cost on the farm than can the same amount of nutrients be supplied with silage. But, as above stated, we cannot be sure of getting these crops, while we can be practically sure of silage; and silage has the additional advantage of being succulent, and thus more nearly supplying ideal conditions for animals to grow and produce than do the dry feeds. Records kept on a number of farms in Minnesota show the average cost of silage to be about $1.80 per ton; including the total cost of producing the corn, getting in into the silo, and the annual cost of the silo.

Value of Silage for Feed. Owing to its succulence and digestibility, silage is a most excellent feed. It enables one to supply, as nearly as practical, summer conditions for his live stock in the winter. On the basis of nutrients contained, a ton of good corn silage is worth about $3 when bran is worth $20. As shown elsewhere in this Annual, silage is a valuable feed, not only for dairy stock and growing stock, but also for fattening cattle. Points a Good Silo Must Have. A good silo must have approximately air-tight walls; the walls must be smooth; it must protect the silage very largely from freezing; should be substantial and attractive; it should be economically constructed; it should be of the proper size and capacity for the farm, and must be conveniently located. The Walls. Of whatever material the silo is built, it is important that the walls be as nearly air-tight as possible, so the amount of waste silage will be reduced to a minimum. It is also important that the walls be very smooth on the inside. If they are rough, the silage in settling will form small air-pockets between the silage and the wall, and bunches of silage will be spoiled. Freezing Silage. It has been fully demonstrated that, if silage is fed soon after it thaws out, freezing does not injure it. However, it is exceedingly difficult and unpleasant to feed frozen silage, and the freezing certainly does it no good; so if it can be protected from freezing, without adding unduly to

Page 66. the cost of construction, it is preferable to have a silo that will protect the silage from freezing. The warmest building-material known is air held in a dead air-space; consequently, a silo with air spaces between its walls is more likely to prevent freezing than is a silo with a solid wall. However, many farmers are using silos with solid walls, made of either lumber or cement, with very satisfactory results. Keeping the silage fed off at a level – or, if anything, lower at the edges than in the middle – having a tight roof, and covering the top of the silage with blankets or hay, are things found to check quite materially the trouble from freezing. Substantial and Attractive. While some types of silos may be built very cheaply, but few people are satisfied with a building that is not thoroughly substantial; and most people want buildings to look neat and attractive. From the standpoint of permanent cost and satisfaction, one will usually be better pleased to pay a reasonable price for a silo, and to get something good, than to get one exceedingly cheap, and never have it quite what he would like. Economical Construction. Like other buildings, the silo offers opportunity for economy in construction to the man who is willing to do his own planning and direct his own labor; and many farmers have built good types of silos, and saved from $50 to $100 or more in cost by so doing. If a man is somewhat mechanically inclined, has time to do it, and enjoys that kind of thing, he can make this saving in almost any type of silo. But a large number of men haven’t much mechanical ability, and can use their time to better advantage at other things. For such men the economical silo is often the one that is built by a reliable contractor.

The Size of a Silo. One of the common mistakes is to build the silo too large in diameter. A cow or steer will consume from 30 to 40 pounds of silage per day. The average feeding period in Minnesota is from 150 to 200 days. If an animal is fed 40 pounds of silage per day for 200 days, it will consume 4 tons of silage. It is better to build the silos reasonably high than to try to get the desired capacity by building them larger in diameter. The same amount of storage capacity can be secured more cheaply in a silo of large diameter, but the loss from using such silos comes from being unable to keep the silage fresh when feeding. Silage is always fed from the top of the silo; and, if the top is left untouched for several days, the silage will spoil. Spoiling, of course, is much more rapid in warm than in cold weather. The silo should not be so large in diameter but that one can feed at least 1 ½ - preferably 2 – inches from the top each day. A silo 10 feet in diameter has about 78 square feet of floor space; so it would have at all times that amount of surface exposed at the top. If 1 ½ inches of silage were taken off of the top of such a silo, one would have 10 cubic feet. A cubic foot of silage weighs about 40 pounds; so the least number of cattle that one could feed from a silo 10 feet in diameter, without waste, would be 10 head, fed at the rate of 40 pounds per day. A silo 30 feet deep is 360 inches deep; and if one fed from it at the rate of 2 inches per day, it would furnish feed for 180 days. It is perfectly safe to build a silo, in most any location, from 35 to 40 or more feet high, and it is a part of wisdom to build at least so high, and only large enough in diameter to give the capacity needed for feeding. If one is contemplating feeding silage in the summer, it will be necessary to figure on feeding at least 3 inches per day; so even a 10-foot silo, by feeding at the rate of 3 inches per day, would supply ample silage each day for 20 head of stock. It is more practical on most farms, to have two silos 12 feet in diameter than to have one silo 16 or 18 feet in diameter, from the fact that the silos smaller in diameter allow more economical feeding. The following sizes of silos are sug-

Page 67. gested: For 10 cows, 10 feet in diameter; for 15 cows, 12 feet in diameter; for 20 cows, 14 feet in diameter; for 30 cows, 16 feet in diameter, such silos to be from 30 to 40 feet high. Location of the Silo. The first consideration in locating the silo is to have it where one can conveniently feed from it; that is, have it located as near as possible to the spot where the bulk of the silage will be fed. Another matter of importance in locating a silo is to have it on the least-exposed side of the barn. There is little doubt but that the same silo will freeze more readily on the north side of the barn than if placed in the more sheltered position on the south side. However, many silos are built on the north side, and give good satisfaction; and we think it is better to have the silo conveniently located in another place than to have it inconveniently located on the south side. Where stock is kept in a basement barn, silos can often be constructed on the upper side of the barn, and thus 10 or more feet of the lower part of the silo be built below ground, where freezing will be very slight. Under such conditions, the silo would be placed on the high side of the barn, regardless of direction.

Foundation. The foundations for all types of silos are built of either stone, brick or concrete. If the silo is to be of brick or concrete, it is absolutely necessary that this foundation be very carefully put in. It is desirable that the foundation extend below frost, if it is possible to go that deep without getting into wet soil. It is impossible to build a brick or cement silo that will not crack, unless it has a good, substantial foundation. In heavy soils it is necessary that the foundation be amply drained by tile or otherwise. The lower part of the foundation should be 1 ½ or 2 feet broad, at least, for an ordinary-sized silo, so it will not be likely to settle in any place because of an uneven footing. There is no loss in putting the foundation down deeply, as a storage capacity from 4 to 6 feet below the barn floor can be used to advantage for silage; as it is not exceedingly difficult to throw silage out of a pit 4 feet deep. Some people make their pits 6 or 8 feet below the feeding-floor; but this, in our judgment, is inadvisable, as it takes too much work to get the silage out for feeding. We mention the foundation in particular, because it is a very important part of the silo; and because, as a rule, whether one builds his silo himself or it is built by a contracting company, the farmer furnishes the foundation.

Kind of Silo to Build. There is considerable controversy, among the manufacturers of different types of silos, as to which is the best form of silo. There are in Minnesota good silos of nearly every make. Among these are the panel and stave wooden silos; solid-wall and hollow block concrete silos; common brick and hollow clay-block silos. We feel that it is much more important that a farmer build a silo than that he build any particular type of silo. Any common type of silos, well constructed, will be found satisfactory; and we would suggest that one build the type of silo that best pleases him, or that he is best able to build under his particular conditions. Both the matter of first cost and annual cost should be duly considered. We submit herewith illustrations and statements regarding several common types of silos in the State. [not shown here] (Minnesota Farmers’ Institute Annual 1911, Jones & Kroeger Company, Winona, MN, Number 24, 1911)