Follow the (ACO) brick road

Springfield firm marks 112th year

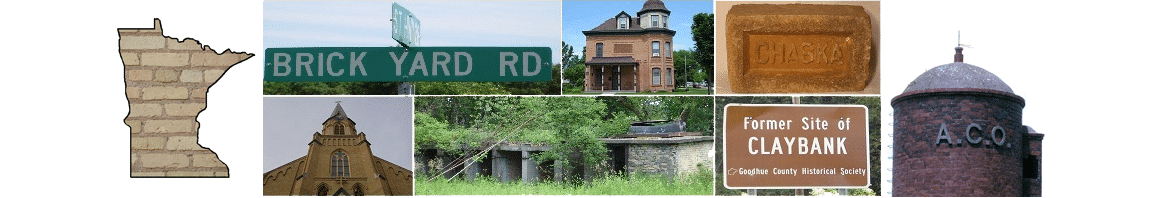

Have you ever wondered what the huge white letters “ACO” represent on the red brick and tile silos that dot the Southwest Minnesota countryside?

Although many of these silos built between 1910-1945 have disappeared in the last couple of decades, ACO silos are still common. At least five still stand within five miles of our home on Lake Sarah in northern Murray County. The longevity of these silos speaks well for the quality of workmanship and the product itself.

ACO silos are most common within a 60-mile radius of Springfield, but I have seen them east of New Ulm, west of Balaton, south of Hwy. 30 and north into the Green Isle, Arlington, Fairfax and Winthrop areas. Possibly the most beautiful still standing is on the Bob and Carol Riecke family farm near Fairfax. A large framed picture of this barn and silo taken shortly after its completion (I think in the 20’s) hangs in the conference room of the Ochs Brick Co. in Springfield yet today.

Many of us have seen those three letters, ACO, on silos for most of our lives, yet don’t know what the letters stand for, much less the story behind them.

Apples, corn & oats

Doris Weber, editor of the Springfield Advance Press, remembers that her father always said, “ACO - apples, corn and oats.”

Her comment takes me back 50 years, when I spent part of a summer working with my brother-in-law’s (Wally Johlfs) construction company. That summer the company installed a large sewer and water project in Yankton, S. D. I was a tender for bricklayer Ole Huness of Slayton.

In those days precast cement manholes were not common, so Ole built them brick by brick. Wally said that most required approximately 3,000 bricks and the largest nearly 10,000. The best brick then cost about 10 cents each; culls cost about five cents each. Ole was fast and I can still hear his Norwegian brogue. “Billy, more mud, more brick.”

One Friday, coming home to Slayton, I noticed a silo southwest of town with the letters ACO. I asked Ole what those letters stood for. Quick as a wink, Ole nonchalantly said, “Always call Ole.” I didn’t believe him, but I did speculate on what they did mean. Allied Co-op Organization? American Cattle Operator?

Not until teaching an inter-active TV class on Southwest Minnesota history did I learn the origin of the ACOs. One of my students from Redwood Falls back in the early ‘90s was Chris Ochs, a great running back and linebacker for the Cardinals. For his presentation, he talked and showed photos of his distant relative, Adolph Casimir Ochs, who founded the A. C. Ochs Brick & Tile Company in Springfield. I was hooked.

Now, like the Burma Shave signs that dotted our two-lane highways from 1926-1963, the American barns that advertised Mail Pouch Tobacco, Hamm’s Dancing Bear, the Jolly Green Giant and Pillsbury’s Doughboy, ACO silos beg our attention.

Take pictures now

In 1992, our son-in-law and his father, Tom and Eugene Hook, removed their 1938-built ACO silo to make room for expansion of their Simmental cattle operation. I was told that the labor cost of erecting that silo was $250. Now, I wish the ACO letters could have been saved. Hopefully, the excellent Brown County Museum and Historical Society will see fit to acquire those three large white letters, ACO, and develop a display of the silos and the A. C. Ochs Brick & Tile Co., now the Ochs Brick Co.

Most historians agree that photos are our windows to the past and that often one picture is worth a thousand words. Such is the case with ACO. Before it’s too late, all of us should make an effort to capture on file this window into our past. Readers are invited to send us a photo of your favorite ACO silos and we’ll print several in the Sailor next summer. Send to: The Sailor, 207 Fourth St., Tracy, MN 56175.

Picturesque backroads

This fall I’ve seen numerous ACO silos. My wife and I explored the backroads of Brown County, particularly Milford and Sigel townships, as we traversed the area along the big Cottonwood River where her relatives bought land and wood lots from the U. S. Government in 1857-58. Five years later, the Dakota Conflict erupted and that area along the Cottonwood and Minnesota Rivers was hard hit, especially Milford Township, where several settlers were killed.

Rounding a bend on the Heritage Road between Iberia and New Ulm, we saw several ACO silos in excellent condition. We located several more on Co. Road 24 from Springfield to Hwy. 15 south of New Ulm that takes you through Leavenworth and Searles. The area around Stark and Hanska and on Hwy. 14, along the Laura Ingalls Wilder Memorial Highway, is also a good place to look. Many are hidden by barns, grain bins, groves, new machine sheds, and houses; some are dwarfed by one or more blue Harveststores or cement stave silos. All, no doubt, have stories to tell.

A silo southeast of Springfield on Co. Rd. 24 is an example. The farmer has left the A and substituted another A while removing the C and O. Maybe an Arthur Anderson?

Just looking at the silos conjures up questions. When was each one built? How much did it cost? How did they build the domes? Are any being used today? Was a curvature built into the tile? Were the red brick houses, barns and outbuildings built at the same time? How many were built? Did they go into South Dakota or Iowa? Which ones used materials produces by German prisoners of war who were transported from New Ulm to the A. C. Ochs plant in Springfield to work during the early ‘40s? The prisoners were said to have been a part of General Edwin Rommel’s famed Africa Corps and were captured in North Africa by General George Patton’s 7th Army and/or the British forces of Field Marshall Montgomery. To find out, I sought out people involved with the present Ochs Brick Co.

112 year legacy

Never have I encountered a nicer, more cooperative and down-to-earth group of people. I visited with Board Chairman, Peggy (Pieschel) Van Hoomissen, at her home in New Prague. Peggy and her husband, Matt, president and CEO, are the company owners. We talked with Matt at the plant in Springfield and spent two hours touring the plant with Sharon Pieschel, vice-president of administration, and plant superintendent, Phil Weller. This time proved to be both educational and extremely interesting.

I also had a chance to talk twice to Mike Pieschel, who owned the company from 1964-1993 before turning it over to daughter Peggy. Mike had worked summers at the A. C. Ochs Brick & Tile plant while in high school and was able to provide a wealth of information about the silos. There was a curvature in the tile. Clarence W. Blue, the son of Springfield contractor A. C. Blue, sold many of the silos. Mike thinks that most prices involved labor and materials, as Clarence W. had close contacts with various crews that erected the silos. Clem Schmid’s crew many as did A. C. Blue and B. J. Engelen. Years ago, Mike had set out to photograph as many of the silos as possible, but somehow the photos seem to have disappeared.

Adolph Casimir Ochs was the founder of the company. Legend has it that Adolph had returned to the area from construction work in California, where he had worked for a contractor who owned a brickyard and that he had often been sent to the yard to help make more brick. Adolph returned to Brown County in Southwest Minnesota, and while swimming in the Cottonwood River with friends, he accidentally discovered a clay deposit of exceptional quality.

Adolph ran the company from 1891 to 1916, when he incorporated with his three sons into the A. C. Ochs Brick & Tile Co. A. C., as president, was pretty much in charge until his death in 1940, whence his three sons took over. Much of the brick at that time was made in beehive-shaped kilns. One still stands near the ultra-modern plant in Springfield for historical preservation. The Ochs boys decided to sell out in 1954 and Elmer Apt, a Fort Dodge, Iowa auto dealer, bought the company. Elmer ran the company for a decade, and during his ownership installed the first tunnel kiln, in which bricks move on platform cars through the tunnel during the firing process. In 1964, Apt sold the operation to “Mike” Pieschel, a second-generation Springfield banker who had worked at the plant while in high school.

By 1989 the Och’s Brick Co. was producing 30 million bricks a year. In a Minneapolis Tribune article that same year Mike was quoted as saying, “If there is one major problem in the brick business today, it’s that there aren’t enough trained brick masons to do as much work as we’d like to be able to do.”

Thanks to a $10 million expansion completed in the fall of 2000, the plant now has the potential to produce 60 million bricks a year.

I was impressed by the improvements during a plant tour this fall. The efficiency obtained through automation, state-of-the-art computerization, ultra-modern technology, quality control programs, lab testing, safety factors, and nearly 100 percent recycling of everything speaks well for the future.

I read recently that the F. W. Woolworth stores managed to survive in the five and dime business for 117 years. The Ochs Brick Company will hit 112 years in a few months. Currently the plant operates two shifts with “the furnaces burning continuously, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” Gradually, like the heating and cooling of the brick, the Ochs Brick Company will realize the goal of 60 million bricks per year.

The quality of the clay is essential to the quality of the brick. The company today uses three separate quarries, all relatively close to the Cottonwood River. The buff colors come from north of Sleepy Eye. One quarry near Courtland provides two colors and the huge site just southwest of Springfield continues to provide the red clay. The original source, just east of the plant, near the sharp bend in the Cottonwood, was abandoned some years ago. The unique glacial deposits of high-quality clay will last far into the future.

Utilizing Mathowitz Construction of Leavenworth for mining and Carlson and Halter from the Springfield area to haul clay and brick, the Ochs Brick Co. provides a huge boost to the local economy. In September and October, a six to 12-month supply of clay is stockpiled at the plant.

No history of ACO would be complete without reference to some of the places built in Southwest Minnesota with ACO brick. They number in the hundreds. A very minute list includes: schools such as Redwood Falls High School, Gustavus Adolphus College, Minnesota State University at Mankato, Southwest State University at Marshall, South Dakota State University, the University of North Dakota, Hamline University, and the list goes on and on. There are several hospitals and commercial buildings including Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing, General Mills, Honeywell, Hormel at Austin and John Morrell & Co., Sioux Falls. One of the largest companies with an exclusive contract for buildings through the country is Kohl’s Department Stores. A beautiful “rich multi-red volcanic looking brick” was developed especially for Kohl’s. The Masonic building in Tracy and the old creamery in Garvin were built in the 1920s with ACO brick. One wall in our home’s basement is a beautiful combination of red, buff, orange, and multi-colored ACO brick. The old Memorial Stadium at the University of Minnesota was built with ACO brick.

I’d like to thank Matt and Peggy Van Hoomissen, Paul and Sharon Pieschel, G. M. “Mike” Pieschel, Phil Weller and Doris Weber. Without their time and co-operation this article would not have been possible. I hope it contributes to the history of Southwest Minnesota and inspires us to open that window to the past with pictures and stories about the ACO silos. (Bill Bolin, History is Life, Southwest Minnesota Sailor, around January 20, 2003, used with permission of the author and the Sailor)