Brick after brick: Job also has spiritual meaning for mason

By Mark W. Olson

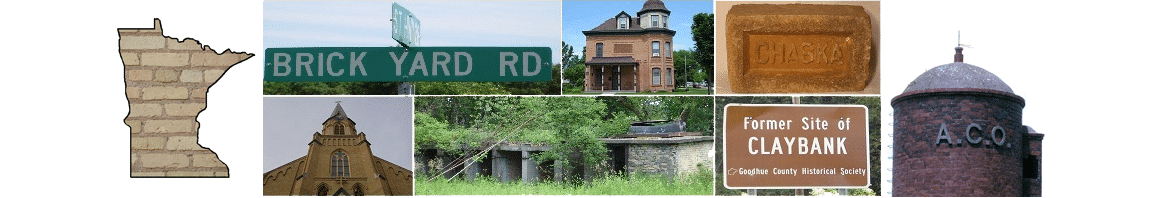

Chaska brick is our town’s pride and joy.

Homes, businesses and churches constructed from the locally produced cream-colored brick can be found throughout the metro area.

“The beauty of the brick work isn’t something that you see on any modern buildings. You don’t see it in any modern brick structures,” said mason Patrick Sieben.

But by 2013, no one would blame Sieben if he never wanted to see another Chaska brick in his life.

That’s the projected year the South St. Paul resident will have completed work on 210,000 to 225,000 face bricks on the Guardian Angels Catholic Church, its adjoining friary and friary garden walls.

First Sieben needs to grind cement mortar that is cracking the brick. Then he’ll replace it with a softer mortar similar to the original mortar used in the 1868 friary and 1885 church. In many places the mortar has worn away – sometimes knuckle deep. (The process of replacing or adding mortar is called “tuck-pointing.”)

The church has also been sandblasted, opening up the pores of a brick to absorb more water, hastening the deterioration.

Church officials emphasize the importance of the restoration. Nowadays, brick walls serve as a façade, with a brick exterior, but steel framework. However, the walls of Chaska’s old brick buildings carry the entire weight of the structure.

So the brick walls of Guardian Angels, up to 4 feet thick, are carrying the entire weight of the 162-foot-tall steeple.

“That’s why it’s important you get restoration done before you have too severe deterioration. Because if water is penetrating, it will go back further and further into the masonry,” Sieben said.

Tuck-pointing

“Part of the reason we have to restore the entire church is the tuck-pointing done in the past,” Sieben said. Previous tuck-pointers used a cement mortar that was harder than the actual brick.

As a result, as the brick expands and contracts with freezing and thawing temperatures, it pushes against the harder mortar. In some cases the pressure pops off the face of the Chaska brick. “It forces the brick to break because the mortar is too hard,” Sieben said.

The test results on the church’s original mortar recently came back, giving Sieben the mix he’ll need for tuck-pointing. It’s a mixture of sand, lime and some cement – but not enough cement to damage the surrounding brick, Sieben said.

Drive by Guardian Angels, and you’ll see parts of the church, and the surrounding walls, wrapped in plastic. In the winter, Sieben is grinding out the mortar. However, he needs to cover the walls with plastic, so the exposed joints don’t absorb water.

While grinding out the old mortar, Sieben will go through an estimated 600 diamond blades. As he’s grinding out the mortar, a vacuum sucks up the dust. At a pound of dust per square foot, Sieben estimates pulling 30,000 pounds of mortar dust from the building.

Then, next summer, he’ll tuck-point the walls with new mortar – a task that needs warmer weather.

Replacement

Approximately 2,500 brick have disintegrated to the point where they need to be replaced. However, the last Chaska brickyards closed down almost a half-century ago. “It’s hard to find good recycled Chaska brick,” Sieben said.

The church is acquiring some of its replacement brick from the city of Chaska, which has stockpiled salvaged Chaska brick from demolished buildings.

“Getting them can be tricky – the city is about the only carrier of them that I’ve found. It’s even harder to get them in good shape. They’re not used anymore, or made at all, so not only is it difficult to get them, it’s difficult to get good ones,” Sieben said.

The original bricklayer has already taken the best side of the brick to face outward, and often that side has been painted, he said.

A portion of the wall surrounding the friary gardens, along Cedar Street, is leaning four inches, and will be reconstructed.

Small contractor

“This is my first Chaska brick project,” said Sieben, who began this project the last week of October 2009. However, he has completed restoration work on two other Catholic churches.

Guardian Angels officials, after checking out other larger restoration firms, decided to go with Sieben, a private contractor.

“His bid was almost half of what other contractors are doing, and it’s largely because he’s doing it over a four-year period of time and he doesn’t have a lot of overhead as a one-man operation,” said the Rev. Paul Jarvis, of Guardian Angels.

Sieben calls the job a “win-win.” “I like big projects, because, for one I know I’m going for a long time, and its steady work, which isn’t always the case in this industry.”

For Sieben, the project also has a personal, faith-related meaning. “I’m a Catholic and I love being a Catholic and for me, this is a way I can help the church. So I look at it as an opportunity to help the church,” he said. “I don’t look at it as a standpoint of how much money I can make. I’m looking at it as how I can make a living and how can I help the church in the greatest possible way.”

However Sieben ponders a time in his life when he works inside a church, rather than outside. Sieben, who has a wife and four children, is pursuing a master’s degree through Ava Maria University. He is considering pursuing a deaconate program, and working with a church as a faith formation director.

“I’m open for, when I finish this project, to see what direction the church would have me move next,” he said.

Tricky brick

What is a Chaska brick? For almost 100 years, Chaska was one of Minnesota’s largest brick producers. Brickyards created countless distinctive cream-colored brick. This brick can be found throughout downtown Chaska, including Guardian Angels Catholic Church. However, Minneapolis and St. Paul also used Chaska brick, and it can be found in buildings ranging from the Grain Belt brewery to the state Capitol.

Why not sandblast? Over the years, many owners have sandblasted their brick buildings to bring back the original cream-color tone. Unfortunately, sandblasting removes the harder outer shell of brick. Think of brick as a loaf of bread – remove the crust, and the bread crumbles – the same as brick.

Bad mortar. The original mortar for Chaska brick buildings was usually a mixture of lime and sand. Over time, this has been replaced with a harder cement mortar. Chaska brick is soft, and expands or contracts with the temperature. (There are more than 500 freeze/thaw cycles during a Minnesota winter, notes mason Patrick Sieben.) Because the cement mortar has little flexibility, the expansion causes the brick to crack and crumble. Sandblasting hastens this cycle.

What can be done? It’s impossible to replace the layer of brick lost to sandblasting, but the cement mortar can be ground out and replaced with a softer mortar (called “tuck-pointing”). Guardian Angels is also replacing some of the more deteriorated brick with salvaged brick from demolished buildings.

Source: Chaska Herald archives

Patrick Sieben

Résumé: Sieben, a contractor based out of South St. Paul, has been a mason for nine years and has also worked on two other Catholic churches – St. Augustine and Holy Trinity in South St. Paul.

Get used to him: Guardian Angels has hired Sieben to work on its north campus. It’s no small task. There are 210,000 to 225,000 face bricks on the church and its adjacent friary and garden walls. Sieben will be tuck-pointing, replacing and reconstructing over the next four years. Tentative schedule: 2010, friary walls; 2011, front of church and steeple; 2012 remainder of church; 2013, friary.

Personal: Sieben and his wife Rebecca have four children, with No. 5 on the way. If that doesn’t keep him busy enough, he’s also pursuing a master’s degree on weekends.

Source: Patrick Sieben, mason

Brick Statistics

210,000 to 225,000: Estimated number of face brick that Sieben is tuck-pointing

600: Number of diamond blades Sieben will use to grind out mortar. Each blade is $50.

30,000: Total pounds of mortar dust sucked up and disposed of (at a pound of dust per square foot of wall)

2,500: Bricks that need to be replaced

4-6 inches: The amount the west church wall is out of plumb, prompting its reconstruction

Source: Patrick Sieben, mason