Tricky bricks: Guardian Angels Crafts Plan for Crumbling Facade

By Mark Olson, Chaska Herald

August 11, 2008

On a recent sunny day, the Rev. Paul Jarvis gave a less-than-sunny assessment of the Guardian Angels Catholic Church exterior.

In some areas, the brickwork of the late-1800s church campus is crumbling. In other areas, the mortar is almost completely gone.

When Jarvis stuck his fingers in the gaps between the bricks of his church, he would have been as happy sticking his hand in an alligator’s mouth. “The really scary stuff is we see these bricks falling and cracking apart, and the face falling off. That’s very serious damage,” he said.

On a parapet, Steve Kingsbury, chair of the church’s Buildings, Grounds and Gardens Committee, points up at a plant growing from a Guardian Angels parapet. “It’s an indication of moisture in brick,” he said.

Inside St. Francis Hall, used for church gatherings, officials note moisture, resulting in mold, on one of the walls. The water leaks through because the brick is porous and cracked, Kingsbury said.

Kingsbury said he thought the sanctuary restoration, completed a few years ago, appeared to be safe. However, Parvis warned, “that’s going to be what the interior of the church looks like upstairs, if we’re not careful and we don’t respond in the next year-plus.”

The buildings committee recently completed a study of church facilities, and the brick restoration issue was the most pressing. “It’s the one that’s staring us in the face. And I mean that literally, because it’s the face of the parish – it’s the front of the parish, and it has urgency,” Jarvis said. (The same study also reviewed the church’s friary building, detailed in a July 27 Chaska Herald.)

So Guardian Angels officials are considering exterior restoration, including the church, friary, and friary wall. The work would essentially tuckpoint (or repoint) every Chaska brick that makes up the church’s north campus.

And it doesn’t come cheap. Officials estimate the cost at $750,000 to $800,000.

Chaska brick

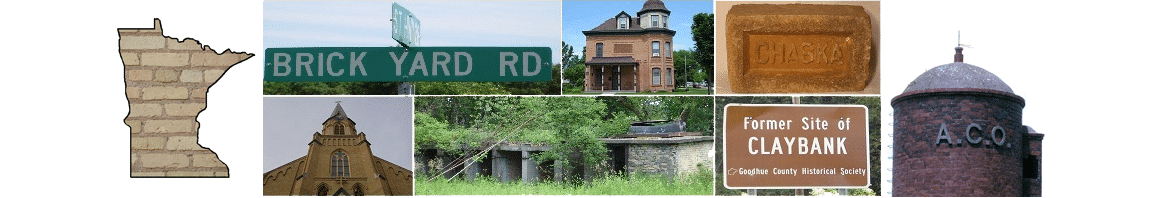

As the façade of the church could be called the “face” of the parish, the cream-colored Chaska brick could be described as the “face” of Chaska.

“It’s how we got started. It’s how we got on the map. It’s how we’re known,” stressed Mayor Gary Van Eyll, a Guardian Angels parishioner. “We have Chaska bricks in the state Capitol for crying out loud – that’s pretty amazing.”

For almost 100 years, the city’s brick industry put the town on the map. Brickyards were scattered throughout Chaska. The remnants of the brick industry can now be found in the form of local lakes such as Firemen’s Lake and Courthouse Lake which served as clay mines.

The city’s brick legacy also remains in its historic core, where many of the city’s residential and retail buildings were constructed of local brick (including the Chaska Herald building, a brick’s throw away from Guardian Angels).

However, countless bricks were exported throughout region. As Van Eyll noted, Chaska brick can be found in buildings as prominent as the state Capitol, as well as buildings throughout the Twin Cities. For instance, many of the buildings in Fort Snelling, currently in dire need of preservation, are made from Chaska brick.

The last brickyard closed decades (years) ago. And now Chaska brick is in short supply.

The city keeps a stockpile of the brick. “We do have quite a few that we have on pallets,” said Interim City Administrator Matt Podhradsky. “We’ve tried to encourage remodeling of, or rehabilitation of, the historic buildings in downtown. We’ve made the brick available for people to be able to have historic Chaska brick to utilize in the buildings – like the livery stable (which houses the Chaska Area Chamber of Commerce and Chaska Historical Society) and the Dunn Bros. building,” Podhradsky said.

As brick buildings were torn down over the past decade (notably the creamery building, and the 1900/04 schoolhouse), the city tried to save some of the bricks.

Besides using the brick for remodeling projects, the city also uses them for park sign pillars and landscaping, as found at the Chaska Boulevard/Highway 41 intersection.

Sandblasting craze

A few decades ago, many historic Chaska buildings, including Guardian Angels church (but not the friary), received the same treatment – a thorough sandblasting.

Owners employed sandblasters to remove years of soot and grime from their buildings. So, while the exteriors looked brand new, the sandblasting substantially aged the brick.

Mark Buechel, historical architect for the Minnesota Historical Society Historical, compares a brick to a loaf of bread. The outside has a hard crust, and once it is removed, the softer interior is more susceptible to damage.

And once it’s done, it’s done, Buechel notes. “And there’s no way to fix it. You just lose a lot of life of the building.” He notes that after years of exposure, bricks develop a new “skin” after sandblasting, but it’s not as hard as the original.

“Sandblasting is a process that should never be used on a brick building,” stresses the city of Chaska’s Preservation Design Manual.

“The general rule of thumb is you want to clean a building as gentle as possible. The first question is, do you need to clean it,” Buechel said. If Chaska brick is used, he encourages using nothing much harsher than a bristle brush, soap and water. However, Buechel stresses that there is “nothing wrong with historical patina. It’s part of the character of the building,” he said.

The U.S. Department of the Interior tells owners rehabbing their building and applying for tax credits that “Chemical or physical treatments, such as sandblasting, that cause damage to historic materials shall not be used. The surface cleaning of structures, if appropriate, shall be undertaken using the gentlest means possible.”

The softness of Chaska brick, “creates its own issues,” said Frederick Whitney, vice president and director of facilities for KleinBank.

KleinBank recently embarked on a restoration of its downtown First National Bank building, which houses Casualty Assurance, Inc.

Two walls of the 1929 building have exposed Chaska brick – appropriate, since bank owners Charles and Christian Klein also owned many of Chaska’s brickyards.

“Thankfully, we have a very good customer in Westin Construction, who works with us quite a bit on our new construction and remodeling jobs,” he said. Besides rebuilding a crumbling parapet, the company worked on the walls, replacing and cleaning bricks.

One side of the building had tar remnants from the adjacent roof of the long-gone Rex Theater. Instead of sandblasting away the tar, crews washed and scraped it off, Whitney said. Even power washing the brick can drill a whole in it, he noted.

Friar Tuckpointing

The second primary brick preservation issue is tuckpointing.

Jarvis notes that the Franciscans, who inhabited the church grounds, “were known for their simplicity and cleverness in making repairs,” he said, referring to the use of cement patchwork. “This, however, is a situation where the simpler quick fix is not the best option.”

Nowadays, mortar with a high concentration of Portland cement isn’t recommended for tuckpointing Chaska brick.

Preservationists suggest a softer mortar, made out of a substance such as lime. This way, as brick expands with the temperatures, it doesn’t crack against the harder concrete. A harder mortar can actually cause the face to explode off a brick.

“We want the mortar to expand and contract at roughly the same rate as brick in the winter and summer,” noted Jarvis.

Modern mortar serves as sort of a glue to hold bricks together like panels, Buechel explained. However mortar used in load-bearing Chaska brick walls serves a different purpose. The mortar allows for movement. It also allows for moisture to work its way in, as well as out.

Paying for it

“There are some things that need to be done prior to (the brick preservation project), or at least concurrent with that, and that is getting our financial house in order,” Jarvis said. “Right now, the typical parishioner at Guardian Angels and elsewhere is really stressed out with gas prices and the economic situation.”

And, Jarvis said, Guardian Angels parishioners have already increased their tithing over the last nine months. “We’ve gone from a typical weekend collection of $7,000 to $10,000 to $11,000 to $14,000,” he said. Part of the increase is due to growth over the past nine months, from 300 households to 800 or 900 households, Jarvis said.

“We still have to look toward the future – what needs to be done this summer, what’s done next spring, summer and fall. And just like in a business, we have to be following a couple of tracks. We have to be looking at what needs to be done immediately in the near term, and also investigating and seeing what needs to be done in the next-to-near term.”

As a result, Jarvis said he is hoping parishioners that have been “well-blessed, for whatever reason in their life, could help out with generous donations” – a point he also stressed in a recent church newsletter.

The brick restoration could be done in a two-step process, officials said. The façade of the church could be done first. However, this alone is an expensive proposition – including the 162-foot-tall steeple.

“We love what our forefathers and mothers, as well as the Franciscan friars, handed on down to us. To practice good stewardship of what earlier parishioners and Franciscans have given us, we just have to use 21st century methods to preserve a 19th century complex,” Jarvis said.