A Successful Test. A Sample Elevator Bin of Tile Tried by Fire. It Easily Stood 2,000 Degrees. It Is Maintained That the New Style of Construction is Better Than Steel and Concrete. The Barnett-Record company have just made a final test of the new tile construction for grain elevators. Two years ago a sample bin was put up near the Shoreham elevator. This was loaded with grain and used through the winter. Last year the Great Eastern elevator company put up a three-tank elevator on the Minneapolis East Side. This elevator has now been used a year. There has been some question as to the amount of fire it would stand and as to the effect of the fire on grain in this style of bin. The construction company had explained what it intended to accomplish and was under guarantee to insure these results. To supplement these tests of a time and of actual use, a fire test was also necessary, and as the Great Eastern people did not care to have the attempt made to burn down their elevator, a section of a bin was erected near the A mill for the purpose.

The Fire Test. It was determined to submit the sample bin to a test that would demonstrate for all time its ability to withstand fire. The thermometer stood at 15 degrees above zero, and the tank being open, water and snow were applied to the inside and allowed to freeze into a cake. Directly opposite this spot on the outside and against the outer wall the builders erected a furnace. Fire was started and kept up to a high point until the pyrometer reached its maximum register, showing a temperature of 2,000 degrees, when the instrument was withdrawn. This intense heat came directly against the part of the wall opposite the iced spot, yet for a long time there was no evidence of it. Not until the fire had been banked did the ice begin to melt and run down and when the last spark of fire had died away some particles of ice and snow still remained unmelted on the opposite side.

A New Type. No extended notice has been made of this type of construction. Barnett & Record were the first to adopt what is known as the hollow tile bin wall. The outside of this wall is the flat side of red vitrified tiling. The tiles are set on edge in a tile base through which binding steel rods run round the tank. On top of these tiles another tile base is placed and the operation repeated. So every alternate row is a cross tile and two tiles on end. In this way there is provided air spaces which are only the length of the tile and are intercepted by the cross tiling. Inside this wall is cemented another row of white, unvitrified tiling with the openings end to end so that the hollow parts of the tiling form continuous air spaces from top to bottom. This is the manner in which the Great Eastern tanks were built. From a distance they have the appearance of steel tanks. They are perfectly round and the plant as a whole presents a very symmetrical appearance. There is not a piece of wood as large as a lead-pencil in this elevator. This style of elevator is particularly useful where there is a fire risk from adjoining wooden buildings. This is demonstrated by the test just made. It is claimed for this type of construction that it takes less money than the concrete form and that it presents a much better appearance. It costs more than steel which is all right for the construction of isolated elevators, but still it is said no other form is able to compare with the tile type in utility, or strength or fire resistance. (The Minneapolis Journal, Monday Evening, March 11, 1901, Page 6)

Tile Tank Elevator. St. Anthony Elevator Company Will Build. Capacity 1,650,000 Bu. It Will Be Located in Southeast Minneapolis. The Cost to be About $225,000. Work Will Be Rushed – Contract Let Yesterday to Barnett & Record. W. H. Dunwoody, president of the St. Anthony Elevator company, yesterday afternoon closed a contract with the Barnett & Record company for the erection of a fireproof grain elevator with a capacity of 1,650,000 bushels of wheat, approximating $225,000 in cost. The company has twenty-five acres at the intersection of Twenty-eighth avenue SE and the Great Northern tracks, upon which they already have elevators No. 1 and 2 with a capacity of 2,000,000. The new elevator is to be built on this property north of elevator 2. It will be accessible to the Great Northern, Chicago Great Western, Northern Pacific, Soo and Minneapolis & St. Louis railways. The elevator is to be erected at once and the contract calls for completion Oct. 1. The construction is to be of absolutely fireproof material. The steel-working house with a capacity of 150,000 bushels, will contain nothing inflammable in its construction. The receiving machinery, the scales and all the working paraphernalia used in a receiving-house will be of the latest pattern. A new feature for Minneapolis will be the employment of electricity entirely as motive power. The amount of horse power of the generators is not yet determined nor whether a new steam plant will be erected for running the dynamos. The new tile construction which the Barnett & Record company used in the erection of the Great Eastern elevator tanks will be used in the new St. Anthony elevator. The twelve tanks will be of tile with a capacity of 125,000 bushels each. The capital stock of the elevator company will be increased to $500,000 and the elevator will be controlled and used by the Washburn-Crosby company, which recently purchased the Washburn mills. The company, which has already a large flour business, shows its confidence in the city as a grain and flour market by the extension of their large plant. (The Minneapolis Journal, Tuesday Evening, April 4, 1901, Page 1)

Let $100,000 Contract. North Star Malting Company. Barnett & Record Will Erect 18-Tank Elevator of Hollow Tile Construction. On Saturday the Barnett & Record company of Minneapolis were awarded the contract for building the grain elevator of the North Star Malting company’s new big malting plant at Eighteenth avenue and Seventh street NE. The contract calls for a capacity of 500,000 bushels. The elevator will be of fireproof construction. The working house will be made of steel and the eighteen storage tanks will be of the new hollow tile construction. The first improvement of the Malting company will cost about $100,000. (The Minneapolis Journal, Tuesday Evening, April 16, 1901, Page 6)

For Five Tile Tanks. Great Eastern Elevator Company Lets $75,000 Contract. Barnett & Record Get It. Will Add 550,000 Bushels to the Elevator’s Capacity – Tile Construction Popular. The Barnett & Record company has just closed a contract for the immediate erection of an addition to the Great Eastern elevator plant of five tile tanks. The plant is situated at Twenty-third avenue SE and Seventh street, and consists of a steel working house with four tile tanks, having a combined capacity of 550,000 bushels. By the addition of five tanks the total capacity will be 1,050,000 bushels. The working house accommodates 150,000 bushels, and each tank 100,000. The contract price is about $75,000. The Great Eastern Elevator company put up the first tile construction tanks ever used in Minneapolis. The new ideas of the constructors, Barnett & Record, have proved feasible, and the company shows faith in tile tanks by making this large addition to its plant which was built only about a year ago. The Barnett & Record company is now constructing the elevator and tile tanks for the North Star Malting company at Seventeenth avenue NE and Second street; the St. Anthony Elevator with tile tanks at Thirty-first avenue SE; the Spencer Grain company wood, steel clad, working and receiving-house at East Thirty-fifth street; and two tanks for the Victoria elevator at Main street and Thirty-third avenue NE. Work is being done of the foundations of each of these jobs. The Victoria company’s plant will be increased 250,000 bushels by the addition of the two tanks. The addition which this company is making to the Cleveland Grain company’s plant will be completed by July 1. (The Minneapolis Journal, Friday Evening, June 14, 1901, Page 6)

Tile Tank Elevator. New House for the St. Anthony Elevator Co. A Washburn-Crosby Company. It Will Be in Southeast Minneapolis and Will Be Rushed for Fall Crop. The Washburn-Crosby company has planned to enlarge its grain storage capacity in Minneapolis and ground will be broken in a few days for another large grain elevator. The elevator will be erected by the St. Anthony Elevator company, a corporation controlled by the directorate of the Washburn-Crosby company, upon a piece of ground adjoining the present plant of the St. Anthony Elevator company in southeast Minneapolis. The new house will be of tile tank construction. The capacity will be 500,000 bushels and the structure will be so built that the capacity can be enlarged later if desirable by building additional tanks. At present four tanks will be erected, and they will hold a trifle over 125,000 bushels each. Barnett & Record have the contract for the new housem (houses). In view of the fact that a heavy movement of grain is looked for this year an effort will be made to rush the building to early completion, to share in the handling of the new crop. The contractors say the new elevator will be ready for operation by the middle of November. (The Minneapolis Journal, Friday Evening, July 25, 1902, Page 6)

Page 25. Fireproof Grain Storage. The Latest Triumph of Burned Clay Applied to Commercial Purposes. The evolution of the modern grain "elevator" is the result of experiments that have been made on a costly scale for the last thirty-five years. As long ago as 1865 the methods of handling and storing grain in large quantities had been brought very near to mechanical perfection. The elevators were built with solid walls of wood, sometimes covered with sheet iron and in rare instances surrounded by brick walls. The most important considerations were how to construct foundations sufficient to carry the enormous weight of the grain bins when loaded and how to build the wooden walls strong enough to prevent them from bursting. A standard wall, six inches thick, made of 2x6-inch scantlings, nailed one upon the other and breaking joints at the intersections, was adopted. It is even used now in the cheaper kind of elevators. Instead of fireproofing, the sole reliance against fire loss was placed upon insurance policies. The rates for these have always been excessive, varying from 2 ½ to 3 ½ per cent, due to the fact that an elevator fire is almost always a total loss, for the grain, if not burned, is destroyed by water, and rarely, if ever, can an elevator be repaired after a fire. These risks vary also according to the external exposure of such struc-

Page 27. tures, and they have always been placed in isolated locations as far as possible. When, as now, banks are willing to advance money on grain certificates representing grain stored in scientifically constructed fireproof receptacles, without the additional security of policies of insurance, it will readily be appreciated what a great success has been achieved in the structures to be hereafter described. The first fireproof elevator was erected at Buffalo in 1869 by the Tifft Iron Works, of that city, after plans made by the late George H. Johnson, engineer. This was the famous Plimpton elevator (Figure 1), and the only one of its kind ever built. It was built entirely of brick. The bins were circular ten-inch walls, built of two courses of common bricks, with two-inch air spaces between. They were banded at intervals of eighteen courses, with cast-iron perforated plates in short sections, which served to preserve the two-inch space between the two courses of bricks, and were tied, one to another, with vertical rods in the air spaces. The form of the bins was shown on the outside, there being no inclosing wall, and the interstices between the bins were also used for storage. This elevator has recently been taken down, in consequence of changes in the right of way of the New York Central railroad. It has always been a paying investment, largely on account of the saving of insurance.

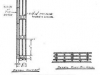

The first use of hollow building tiles in the construction of grain elevators was on the wooden elevator of Vincent, Nelson & Co., at Archer avenue and South Branch, Chicago, in 1872. But the tiles were only used to inclose the "cupola" to prevent it from taking fire from adjoining buildings. The bins were inclosed in brick walls. In 1890 elevator A, of the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad Company, at Sixtieth street and Hudson river, New York city, was built in the following way: The first-story inclosing wall is brick, and the bins and cupola are covered with salt-glazed hollow tiles. Several others have been built since then in the same manner. The success of the Plimpton elevator induced Ernest V. Johnson, son of George H. Johnson, to experiment on the construction of circular bins of hollow tile, instead of brick. In this he was assisted by James L. Record, an elevator architect of Minneapolis. In 1899 they built a grain tank at their own expense as an experiment, on the grounds of the Osborne-McMillan Elevator Company, at Minneapolis. It was twenty feet in diameter and sixty feet high, with a capacity of 20,000 bushels. Figure 2 is the working drawing from which this tank was erected, which, being very complete, does not need further description. It was erected during one of the coldest Minneapolis winters, and was filled with grain thirty days after completion. The test was successful, and it has been in use ever since. It was also tested for pressure and fire-resisting qualities, and an intense fire on the outside had no effect upon the grain within. In less than a year after this they built four supplementary tanks for the Great Eastern Elevator Company, at Minneapolis.

Figure 3 shows these tanks in process of construction, the contract being taken by the Barnett & Record Company, of Minneapolis. They stand isolated one from another, and each is forty-six feet in internal diameter and eighty-five feet high, with a capacity of 100,000 bushels, the weight of grain in each tank being 2,800 tons. They were built with a single wall of six-inch hollow tiles, line with two-inch split furring tiles on the inside. The courses of six-inch hollow tiles set on end, each having four cells, were alternated with courses of 4x6-inch tiles, made in the form of a continuous trough and laid on their backs. Flat steel tension bars were set in the troughs on edge, three being used near the bottom and two in the upper part, and these were buried in cement grout. The six-inch walls were lined with two-inch furring tiles on the inside. The tanks were built on cut-stone water tables and finished on top with tile roofs formed of "T" irons and book tiles. The grain is handled by one set of travelers in the ground underneath and one set running through the tops of the tanks from the old elevator building. After the erection of this plant Mr. Johnson adopted a form

Page 28. of construction for all tanks, as shown in Figure 4, with two-inch salt-glazed furring tiles on the outside. They are secured as the wall goes up with galvanized steel anchors. In 1900 the Barnett & Record Company built a nest of eighteen tanks, with ten intermediate tanks filling the interstices between them, for the North Star Milling Company, at Minneapolis. Figure 5 shows the work in progress shortly after it was commenced, and illustrates the method of building as shown in Figure 4. The tanks are twenty-two feet in internal diameter and eighty feet high. They form, with a power house, a complete elevator system, with a fireproof cupola built on top of the tanks. Figure 6 shows a row of completed storage tanks attached to a flour mill at Detroit. They are connected with the mill by systems of endless belts at top and bottom. The cornices around the tops of these tanks are built of machine-made salt-glazed hollow tiles. There is now being erected at Chicago a system of storage tanks and elevators for the Northwestern Yeast Company. They are similar to those of the North Star Malting Company. There are twelve tanks, twenty feet in internal diameter and eighty-five feet high, with five intermediate tanks. They will have their own independent elevator, which will also be fireproof. Figure 7 shows one of the concrete hopper bottoms of these tanks, ready for carrying up the outer wall. Figure 8 shows the commencement of the tank walls before setting the internal scaffolding.

Besides those above referred to the following plants have been erected according to this system during the last two years, including some now in process of erection: For the St. Anthony Elevator Company, at Minneapolis, 12 tanks 50 feet internal diameter and 90 feet high completed, and four of the same size now being erected; for the Victoria Elevator Company, Minneapolis, 2 tanks of the same size as those last mentioned; for the Wisconsin Malting and Grain Company, Appleton, Wis., 9 tanks 22 feet internal diameter and 80 feet high; for the St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad Company, at Rosedale, Kan., two tanks 46 feet internal diameter and 86 feet high, and three more under construction, and two tanks 50 feet internal diameter and 68 feet high; for the Pabst Brewing Company, Milwaukee, fourteen tanks 14 feet internal diameter and 70 feet high; for Bernard Stern & Son, Milwaukee, nine tanks 19 feet internal diameter and 85 feet high. There are also now being built for the Canadian Northern Railroad Company, at Port Arthur, Canada, a cluster of eighty tanks 22 feet internal diameter and 80 feet high. The hard-burned hollow building tiles used in the grain tanks erected for the North Star Milling Company, the St. Louis and San Francisco elevators at Rosedale, Kan., and for B. Stern & Co., Milwaukee, were made by the H. B. Camp Co., at Greentown, O. For all the others they were manufactured at the National Fireproofing Company’s works, at Ottawa, Ill. These, like most of the fireproof building material made west of New Jersey, were all made through dies attached to vertical steam presses.

This, which is the standard form of press now used by all sewer pipe manufacturers, was first employed in Toronto, O., about forty years ago. The first vertical steam press was imported from England by Mr. Carlisle, of Toronto. It has been greatly improved by American machinery manufacturers. Hollow building tiles were first made on a vertical press by John Francy, of Toronto, in 1879, for the floors of the Cook county court house, Chicago. The second fireproof building for which the hollow tiles were made on a vertical press was the ten-story Montauk block, at Chicago, erected in 1881, which has just been taken down to make a site for the new First National Bank. The vertical press makes a harder and more compact body than any of the horizontal presses and works quicker. It was for this reason that it was possible to make hollow tiles with very thin walls out of high grades of fire clay. Readers of The Clay-Worker are doubtless familiar

Page 29. with the numerous other uses to which the vertical sewer pipe is put. Hollow block fireproofing is burned in down-draft kilns such as are used for sewer pipe, but without salt-glazing, unless they are required for external exposure. Even then salt-glazing is only required for appearance, because fire clay, when run through a vertical press and hard-burned, is weather-proof. The Johnson & Record grain bins are covered on the outside with salt-glazed split furring tiles to protect the grain from the effects of external sun heat or fire. These furnish an additional air space and also improve the appearance of the bins. (The Clay Worker, Peter B. Wright, T. A. Randall & Co., Indianapolis, January 1903, Volume XXXIX, Number 1)

William R. Sinks, superintendent of the construction department of the Barnes & Record company, is inclined to the view that the use of concrete is in a sense even yet experimental. "To my mind," said Mr. Sinks to-day, "the most important factor militating against the use of concrete in the construction of grain elevators, lies in the fact that there is about it a modicum of uncertainty. One knows the material, what it has done and what should be expected of it. In using it one calculates even beyond the scope of the engineer in an ordinary work. The effect of the slightest possible settling of the ground, the lateral pressure on the tanks from the interior, the proportionate increase of lateral pressure in the drawing out of the grain, these and numerous other points may be reduced to calculations so accurate and so minute as apparently to eliminate from the work every iota of chance or uncertainty. Yet, when one leaves a work of this kind, he cannot be free from the feat that all is not right, that somewhere in the chain there is a weak link. He carries a nervous fear that somewhere it may break, as if often does in places and under circumstances most unexpected.

"The arguments favoring concrete for grain elevator construction are brief but weighty. Such structures cannot decay, time only hardens them and they require no insurance. As a matter of fact, however, concrete is no such fire-proof material as is generally supposed. When stone, cement and water unite, chemically the water does not leave by evaporation, but in the adhesive process becomes absorbed into the whole remaining in different chemical form. Given sufficient heat and this assumes the form of gas and passes off. Five hundred degrees of heat will cause some preliminary disintegration. Nine hundred degrees will totally destroy the compound, returning it to a rude, irregular, granular form. I do not look for much more construction of concrete tank houses. Personally I am pretty well committed to the use of tile. These tile tank houses that have gone up in Minneapolis are as indestructible as the ingenuity of man can make them. The tile burns for two or three days in a heat equal to 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit, in the process of manufacture. About two years ago we made a test here that attracted the attention of the engineering world. We built a tank near Pillsbury A mill and a furnace next it, and succeeded in directing 2,000 degrees of heat against the side for hours without the slightest effect. This I believe to be the material that will enter into all the big terminal houses of the future." (The Minneapolis Journal, Thursday Evening, May 7, 1903, Page 8)

The three plants of the H. B. Camp Co., formerly controlled by H. B. Camp, are now under the control of the National Fire Proofing Co., although the name of the company is still retained. (Brick, Kenfield-Leach Company, Chicago, April 1904, Volume XX, Number 4, Page 179)