ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE

Minnesota Educational Institution Which Is Doing Excellent Work

HAS BEAUTIFUL LOCATION

Was Built by Rev. Rupert Seidenbush, and Is Under the Control of the Benedictiness.

For some ten or a dozen miles west of St. Cloud I sat looking out of the window of the Great Northern and watched the Minnesota farmer trying to handle the biggest crop that was ever raised since Adam emigrated from Paradise and came out West to grow up with the country. Then, all of a sudden, the conductor announced “Collegeville,” and the train stopped, although there was nothing in sight but a farm house and what seemed to be a large tool chest, such as section gangs sometimes use, though on inspection it turned out to be the depot. A large stage coach was also waiting, and, in the vernacular which is popularly associated with both beer and transcendental philosophy, the driver announced that he would take me to the college, bag and baggage, all free of charge.

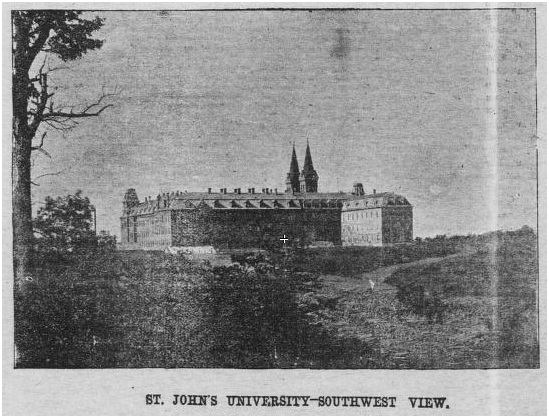

I hopped in immediately, before he had time to withdraw his generous offer, and the other passengers did likewise. Then the whip cracked and we dived headforemost into a mass of hills and woods. Up hill and down hill, the road twisted and turned, nothing but woods in sight, underbrush, young sapling growth, old storm-scarred veterans. The country looks as if on creation day some Titan or giant having the contract of filling up that neighborhood, dropped one huge wheelbarrowful of sand and gravel there after another, not in any regular order, but just as chance happened, and evidently night came before he had time to smooth the ground down and level it, and so each wheelbarrowful lies there to this day as a little hill by itself, except in places where he happened to drop a dozen or more one on top of the other. The driver informed us that the college owns some 2,200 acres of land there, mostly scenery, hills, woods and lake.

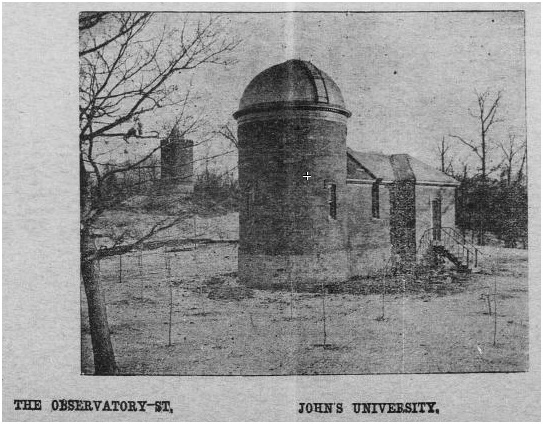

After driving about a mile, we saw before us on a high hill a tall and massive round tower, built of brick, with lofty battlements. It looked as if it might be the stronghold of some medieval robber baron, but it turned out to be merely the water tower of the college. Its size and construction are such that it would be a credit to the water works of a small city. On the same hill there is still another structure which, however, bears all the earmarks of an astronomical observatory.

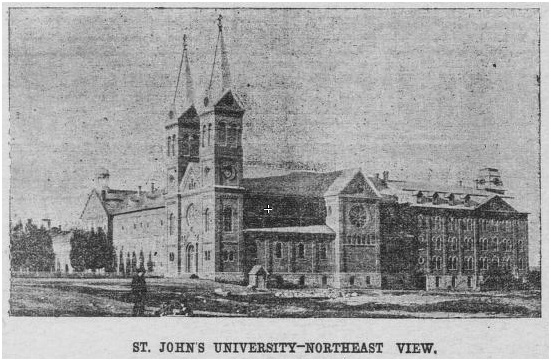

From the top of this hill one has a fine view of the college. It is located on a narrow ridge of land between two bodies of water. On the south side of this ridge is a beautiful little lake, surrounded by hills and woods. It is called Lake Sagatagan. On the north side is a large pond, formed by a dam across a brook, called the Watab. The main building is a huge structure, five stories high, built in a rectangle around an inner court. The front of this rectangle is 360 feet long. This building serves as monastery, college, university, seminary and dormitory for the students, of whom there are usually from 250 to 275 in all. There is a preparatory department for boys from twelve years upwards. The collegiate department compares favorably with that of other Western colleges and universities, offering thorough courses in classical and modern languages, science, mathematics, philosophy, etc. The commercial course is popular and offers a thorough training in book-keeping, stenography, typewriting and kindred branches. The seminary prepares students of theology for the ministry.

The rules affecting the discipline of the students are strict without being irksome. There is no chance of getting through without hard work. The student who comes here merely for the sake of having a good time will be disappointed. Still there is no lack of recreation. On the lake there is a small fleet of boats for the use of the students. Fishing is good in season, and so is skating. The customary collegiate games and sports are cultivated and encouraged. A large gymnasium, with ample room for hand ball, basket ball, bowling, and the common gymnastic exercises is just being completed. A large three-story fireproof library is also in course of construction.

The monastery and college of St. John’s is one of the foundations of the Benedictine order. There belong to this monastery about 100 monks and 35 lay brothers. The greater part of the monks are working as pastors in different parishes throughout the state. The lay brothers are mostly occupied with manual labor in and around the monastery. In the monastery, life is one continual round of work and prayer. Every morning at 3:45 there is a clanging of bells and gongs and a shuffling of many feet along the corridors. The visitor, as he starts from his sleep in bewilderment at the unwanted noise and unearthly hour, is apt to imagine that the building is on fire, but it is only the members of the order hastening to the chapel for morning services. At 3 p.m. they are again called together in a similar manner, and again at 7:30 p.m.

The chapel is really a church of considerable dimensions, and occupies the northeast corner of the rectangle. It serves not only for the use of the students and monks, but also for a small congregation composed of farmers living in the neighborhood. The interior decorations of this church are exquisitely beautiful.

In the evening from 6 to 7:30 is the period of recreation for the members of the order, and one may see them scattered in groups about the verandas and grounds talking and laughing and having the jolliest time imaginable. The scene is bound to give the impression that the monastic life must be conducive to a cheerful disposition. The younger members occupy themselves with bat and ball, and sometimes some bearded monk will hit the ball a whack or two just for old-time’s sake. To see them cutting across the diamond, with their long black habits flying around their feet, and the cowls flopping at their backs, is a scene that would strike even an hypochondriac as irresistibly ludicrous.

The Benedictine order, to which this monastery belongs, is the oldest organization of its kind. It was founded by St. Benedict, who was born at Norsia, not far from Rome, in the year A. D. 480. People living some sort of a monastic life have always been common in Oriental countries – and were not unknown among the Jews before the coming of Christ. Among Christians the monastic life found numerous adherents from the very first years of the church. Such men lived mostly as hermits, sometimes also in small communities, but generally without any rules or organization. Then, too, in accordance with the well known Oriental disposition their life was mainly one of contemplation. In this respect, St. Benedict worked a complete change. He collected a body of monks around him and formed a strong organization under a set of rules, divided into seventy-three chapters. The forces that had been scattered and devoted mainly to contemplation, he organized for united and energetic activity in behalf of Christianity and civilization.

The work of St. Benedict was indeed providential – Christianity and civilization were both in danger of being wiped out of existence. Some special force was needed to preserve them both and St. Benedict organized this force.

Attila, the Scourge of God, as he styled himself, had swept with his heroes down from the plains of Western Asia and burst like a deluge into the Roman empire. Attila and his Huns had indeed disappeared in a sea of blood and ruin, but the old Roman empire was crumbling to pieces. Warlike Germanic tribes, Goths, Vandals, Franks and Burgundians were invading it from all sides. These people had many good qualities, boundless energy, an indomitable courage, but they were still half savage. Their chief delight was war and its spoils. Cities were sacked and burned. Provinces were depopulated. Civilization disappeared; barbarism took its place. It was clear that unless those forces could be won for the support of Christianity and civilization, they would destroy and exterminate both.

This was the work for which the Benedictines were called. They established schools and monasteries where Christian teachers were trained and where the old classic learning was preserved. They strengthened the Christian faith among the native population, overcoming the last remnants of paganism and finally they won over the Germanic conquerors themselves.

The order grew rapidly. Before his death St. Benedict sent St. Placidus to Sicily and St. Maurus to France. Benedictines were the apostles of Bergundy, Flanders, Holland, England, Switzerland, Germany, Norway and Sweden. In all the Benedictines converted some thirty kingdoms and provinces to Christianity, and when they had converted a province their work had but just begun. The people were still imbued with pagan ideas which it took generations to eradicate. All they had learned was war and a rude kind of agriculture. It was the endeavor of the monasteries to spread as much learning as the times would permit, to train men in the various handicrafts and to teach improved methods of agriculture. Each monastery had its own farm lands, the cultivation of which served as an object lesson for the country people. The monks cleared forests, drained swamps and built bridges. They planted the monastery in a desert and around it grew a village which increased to a town; then became a flourishing city. Such is in epitome the history of many a large European city of today.

A Benedictine, the great Alcuin, teacher of Charlemagne, was the founder of the great Paris university, wherein at one time 30,000 students received instruction. In fact nearly all the great universities of the Middle Ages, among them Oxford, were founded by the Benedictines.

It was slow work, reclaiming the people of Northern Europe from warfare and winning the mover to the arts of peace. The feudal lords preferred to rob and plunder as freebooters. The undaunted monks preached divine retribution with a zeal that made many a noble freebooter falter and repent. And if all efforts failed and the city was turned into ruins and ashes, the monastery was held sacred and inviolable. Its treasures of art and learning were safe against fire and pillage.

But not always safe. At times fierce heathen Asiatic tribes related to the Huns made incursions that extended even to the banks of the Rhine. Moving swiftly on horseback from place to place they slaughtered and burned everything before them. Then, when the distant glare of burning villages announced their coming, the peasants would flock to the neighboring monastery to seek protection behind its massive walls, and it was nothing uncommon if on the following morning the monks took up sword and spear and with the men of the countryside marched out to drive back the savage foe or die in defense of home and altar. A very picturesque view of the activity of the monks in the early middle ages has been given by Scheffel in his novel “Ekkehart,” which has also been translated into English.

And if on such occasions they did use the sword effectively it is not to be wondered at. Most of them were probably the sons of men that enjoyed a good fight better than anything else. Many of them had spent years in the camp and on the battlefield before they felt themselves called to the monastic life. Princes and kings often gave up their titles and honors to become simple monks. Up to the fourteenth century the Benedictine order had received into its ranks twenty emperors, forty-seven kings, twenty sons of emperors and forty-eight sons of kings, and at one time the order had as many as 37,000 houses, or monasteries. At present the order is but a shadow of its former self, still it numbers 6,000 or 7,000 members, and is spread all over the globe. During the last twenty-five years it has gained very rapidly, and at the present rate it may before long regain its former standing.

The first Christian missionary that ever crossed the Atlantic to convert the natives was the Benedictine Don Bueil, of Catalonia, who came to America with twelve other priests in 1494. The first Benedictine monastery on the American continent was founded at San Salvador, Brazil, in 1582.

In 1846, the Rt. Rev. Abbot Boniface Wimmer came to the United States with a colony of Benedictines and located in Pennsylvania, where he built the monastery of St. Vincent’s. Soon other monasteries were founded until the Benedictine order in the United States now counts among its members two bishops, thirteen abbots, about 600 monks and 350 lay brothers. It owns and conducts fifteen monasteries and sixteen colleges. St. Vincent’s, Pennsylvania, is the largest Benedictine monastery in the world.

In 1856 Abbot Wimmer sent several members of the order to begin a foundation in Minnesota. They located at first near St. Cloud, which at that time consisted of only a few frame houses. In 1865 the present location on Lake Sagatagan was selected. The first abbot was the Rev. Rupert Seidenbush, who was succeeded by the Rev. Alexius Edelbrock, who in turn was succeeded by the Rev. Bernard Locnikar. The present abbot is the Rev. Peter Engel, noted for his learning and geniality.

Besides the large main building, library, gymnasium, waterworks and observatory, there is also a large steam-heating plant and an electric light plant. A farm and an extensive garden belonging to the monastery supply the greater part of the provisions required for monks and students throughout the year.

The college, surrounded as it is by lakes and woods, has an ideal location. Even in the hottest part of summer the air here is fresh and invigorating. The college is one and one-half miles from Collegeville, and four miles from St. Joseph. Collegeville being but a few miles from the important town of St. Joseph is used only as a stepping-off place for people who wish to go to St. John’s. Many visitors come from week to week, and they are always received by the prior, the Rev. Herman Bergmann, with a cordiality that is fully in keeping with the beauty of the place.

Source:

The Saint Paul Globe

Sunday Morning, August 18, 1901

Volume XXIV, Number 230, Page 5